So what does the London Bridge look like?

What about the one before this one? That bridge is the "London Bridge" that was dismantled, exported, and reassembled at Lake Havasu in Arizona. But that one isn't the medieval bridge, either. Designed by John Rennie and built by his son, it was completed in 1831 as a replacement for the medieval bridge. The medieval bridge was dismantled utterly after the "New Bridge" was opened, and aside from a few carved objects made as souvenirs from some of the original pilings (and various pieces of stonework that were actually eighteenth-century additions to the original bridge), nothing remains but pictures.

It's impossible to say when the Thames was first bridged at that location. Evidence from Roman times (consisting mainly of Roman coins found on the riverbed during the building of the 1831 bridge) suggests that the Romans might have built a bridge, but it is equally possible that the coins might have come from the sinking of a ferry. Also found were some iron "piling tips" but these might have come from any of several wooden bridges which were built in the last few centuries of the first millennium.

The earliest reference to a bridge is in a Saxon record; it was mentioned as an execution site for a witch during the time when one Aethelwold was bishop of Winchester, which would have been sometime between 963 and 984. Wooden bridges, such as this one, were never intended to be really permanent. They fell down, burned down, were torn down, and otherwise required periodic replacement. One in particular deserves notice because an incident in 1014 is thought to have inspired the famous nursery rhyme about London Bridge.

The story is that one Olaf sailed up the Thames with his fleet of longboats. For the Norsemen (who thought of rivers as highways, not barriers) the bridge was a navigational obstruction to be removed, and he proceeded to do just that. He had the piers of the bridge tied to his ships and, rowing downstream (and with the tide), tore the superstructure down.

The Norse bards immortalized this great deed as follows:

London Bridge is broken down,/ Gold is won, and bright renown./ Shields resounding,/ War-horns sounding,/ Hildur shouting in the din!/ Arrows singing, / Mailcoats ringing - / Odin makes our Olaf win!

During the times that no bridge spanned the Thames, there were ferries. We know of one of these because of the charming story of one of these ferrymen, named John Overy (or Audrey). John was penny-pinching enough to stage his own death, in the hopes that the household's obligatory 24-hour fast would help stretch his food stores. The plan backfired when his household instead decided that this was an occasion for feasting, not fasting. When John rose from his coffin to protest their wastefulness, some bystander, thinking that the corpse had been possessed by a demon, brained John with an oar. Some versions of the legend add that John's daughter's fiancÚ set out to spread the news, but tumbled from his horse and was killed. In her grief (presumably for the fiancÚ, not the father), Margaret Overy sold the ferry business and established a religious house, to which she retired.

In due time, the wooden bridge was rebuilt, and came to be administered by the Church of St. Mary Colechurch, the church in which Thomas Becket was baptized. (It was common practice in medieval times for a religious house to build a bridge and support itself, and the bridge, on the revenue from tolls.) In 1176, it became obvious to just about everybody that no more Vikings were going to come sailing up the Thames to tear down bridges, and the time had come to build a permanent bridge in stone. The good brothers appointed Peter of Colechurch as the builder, and Henry II thought well enough of the idea to levy a tax on wool products to help pay for it. (This tax led to the legend that the foundations of the bridge were laid on bales of wool).

The bridge was actually built on nineteen piers in the river. Each pier was formed by driving a ring of elm piles into the riverbed, filling the area inside with rubble, and then laying a floor of oak beams over the result. Additional piles were driven in to surround the pier with a protective structure called a "starling" or "sterling."

Before the bridge was entirely completed in 1209, sections of it had already fallen down and been repaired, which suggests to me that the builders were learning how to build bridges as they went along. (Sections of it had also burned and been repaired. "How could a stone bridge have burned?" I hear you ask. It would either have been the structure supporting the arch segments as they were being constructed, or perhaps the mixture of straw, earth, and dung which covered parts of the stonework during the winter to reduce the damage done by freezing.)

However it was accomplished, the result was a bridge that would last for a long time. The piers were so well constructed that, six hundred years later, they were as serviceable as the day they were built. The decision to demolish and replace the bridge was prompted not by any structural deficiency but by the need for a wider bridge, and the ill effects of the bridge to the Thames itself.

For the bridge was, at times, less a bridge than a causeway with culverts. Its piers blocked about forty-five percent of the river's flow at high tide when it was built, and more than that when the water level dropped below that of the protective barriers, or "starlings," that were built to support and protect the piers. As the bridge got older, the starlings got bigger and bigger, until by the eighteenth century, only a fifth of the river could flow unobstructed under the bridge at low tide.

As if that weren't enough, the tideway would eventually become even more encumbered with additional obstacles to the flow. In fact, these obstacles were designed to harness the flow itself. In 1582, water-wheels were installed under the two north arches to drive pumps that delivered the river's water to the city's water works. Under the two south arches, water-powered grain mills were installed in 1591.

Because the Thames was (and is) a tidal river, its level varied greatly from hour to hour. (In 1114, it was once so low that even children could wade across.) The difference in levels between the upstream and downstream sides if the bridge could be as much as six feet. "The London Bridge was for wise men to pass over, and for fools to pass under," the saying went. Boatmen brave enough to "shoot the bridge" were often capsized as they went over the falls. For boats carrying passenger, the usual procedure was to have them disembark on one side of the bridge and transfer to another boat on the other side of the bridge.

On the ninth pier out from the city, Peter designed a chapel. It was dedicated to the memory of St. Thomas Becket, who had been canonized in 1173, three years before the bridge was begun. Besides honoring one of St. Mary Colechurch's own, it was intended from the start to be a sort of cash cow for the church. Pilgrims traveling to Canterbury from the north of England were sure to cross the Thames via the bridge, and what could be more natural than to say a few prayers, and leave a few pence, at the saint's chapel?

Two other structures originally planned for the bridge were two defensive towers, one near the south shore and the other overseeing a defensive drawbridge near the bridge's midpoint. The latter tower became famous as the place where the heads of famous traitors were impaled on pikes for general examination by the populace. We don't know when this charming practice started, but its earliest victims mentioned in print (in 1305) were the Scottish rebel William Wallace and some of his lieutenants. Among the many famous heads to subsequently adorn the bridge were those of Jack Cade, who sparked a peasant rebellion in 1450, and Roger Bolingbroke, who fell into the bad graces of the Bishop of Westminster and got himself executed for witchcraft. And who could neglect to mention Guy Fawkes, whose "Gunpowder Plot" in 1605 is commemorated to this day? But perhaps the tower's most famous display was the head of Thomas More, whose refusal to accommodate King Henry VIII resulted in his execution in 1535. His head was said to have stayed on the bridge for months in a pristine state, without a trace of decomposition, before it was eventually reclaimed by his family. Henry had his revenge, of sorts, when the bridge chapel, dedicated to that other St. Thomas who incurred the wrath of a King, was deconsecrated, defaced, and eventually turned into a commercial property.

When the drawbridge tower was finally dismantled in 1577, its need having waned during those less tumultuous times, the display of heads was moved to the South Tower. The practice was not discontinued until the demolition of that tower in the eighteenth century.

As originally built, the bridge was about twenty feet wide, ample by the standards of the day. But it wasn't long before the bridge became prime real estate for building. We know that there were extensive buildings on the bridge by 1212, only three years after the bridge was finished. This is because those buildings caught fire that year, resulting in history's greatest bridge disaster. It happened because when the southern end of the bridge caught fire, thousands of Londoners rushed onto the Bridge to observe it. Northerly winds blew sparks onto the buildings on the Bridge's northern end, and these too caught fire, trapping the onlookers between the two conflagrations. In the ensuing panic, hundreds were said to have leapt into the water and were drowned. Hundreds more tried to excape in boats, but so overloaded them that the small craft sank under their loads, drowning more. Those who remained on the bridge were incinerated. The casualty rate was reported as three thousand, surely an exaggeration, but even if the figure were a tenth of that, the disaster would have still had the greatest loss of life in the history of bridges.

But the buildings were promptly rebuilt. The reason for the bridge's popularity was two-fold: an endless supply of water (from the river) and easy disposal of sewage (into the river). Such conveniences were rare in medieval London. (It must have been a relatively healthy environment, because of the thousands of victims of London's Great Plague of 1665, only two were residents of the Bridge.)

The buildings on the bridge reduced its width to as little as ten feet in places. Its narrowness impeded traffic but hardly stifled it. Enough roadway was left to enable even a joust to be held on the bridge in 1390, when the Scottish knight Sir David Lindsay was challenged by the English ambassador to Scotland, Lord Wells. Sir David unseated and injured Lord Wells, but showed his chivalric mettle by visiting Wells in hospital every day until the latter's wounds were healed. The popular Sir David was later nominated to the post of Scottish ambassador to England.

While the nobility was tilting on the bridge, the boatmen were tilting beneath it, shooting the bridge while plying their "lances" at stationary targets on the bridge starlings.

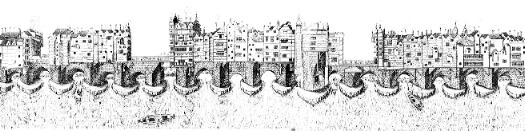

The earliest period representation of the entire bridge is from about 1553, at which time there are houses on the entire stretch of the bridge (except for gaps by the chapel and where the drawbridge was). There were both shops and residences, with two or three stories. Some even had cellars, below the level of the roadway. Often the houses on opposite sides of the bridge were connected with stabilizing beams, walkways, and eventually entire upper stories, resulting in parts of the bridge becoming tunnels. By and by, the bridge became completely lined on both sides: it was said to have been possible for a pedestrian to go halfway across the bridge unaware that he was on a bridge at all. As these buildings eventually became decrepit, they were increasingly replaced with larger, longer buildings of a uniform architectural style. Occasionally these blocks caught fire, leaving large gaps in the line of buildings on the bridge, before being replaced. It was one of these gaps, curiously, that prevented the Great Fire of London in 1666 from crossing onto the south shore of the Thames.

One of the last major modifications of the bridge in the 1500's was the demolition of the Drawbridge Tower (mentioned earlier). Its place was taken by a new residential building prefabricated in Holland and fitted together entirely with pegs and dowels. It was called the Nonesuch House, was the marvel of its time, and quickly became the most desired residence in London.

Until 1750, the London Bridge was the only river crossing in London. But once the Westminster Bridge was completed in that year, the old bridge came to be regarded as an unsightly derelict from medieval times and ripe for rebuilding. Its buildings had gone to seed, its location no longer desirable now that piped water became available elsewhere (due in large part to those water-pumps installed back in 1592). It was clear that the buildings had to go, the road widened, and the waterway improved. All this was completed by 1763, under the direction of the Swiss-French engineer Charles Labelye. For the first time since the bridge had been built over 500 years before, a Londoner could look out on a bridge unimpeded by any edifices. Most of the upper stonework had been replaced, and the piers greatly expanded to carry the added roadway. And one of the piers near the bridge's center was entirely removed and its two adjacent arches replaced by a larger single arch.

The intent of this last modification was to improve navigation on the river, but its effect was to nearly destroy it. The river water, pouring through the gap formed by the pier's removal, began to scour the river bottom, carrying away the silt and threatening to undermine the adjacent piers. Whenever gravel was dumped into the hole to replace the silt, the water washed the gravel downstream, eventually forming a sort of sandbar, or gravelbar, that practically blocked the waterway at low tide.

The old bridge, even though still structurally sound, was doomed. The London City Council put out requests for designs for a new bridge. George Dance the Younger proposed twin bridges, each with its own drawbridge. Thomas Telford envisioned a great single arch, made of cast iron, to span the river. But the design that got the nod was one that wasn't even one of the top three finalists. John Rennie had convinced the House of Commons (which had the final say) that his four-pier, five-arch stone design was the one to build. Rennie's bridge, built just a few yards upstream from its predecessor, was opened in 1831 to great fanfare. By the end of the next year, the old bridge was gone, even the piers and their massive foundations. The pilings driven in by Peter of Colechurch's builders were extracted from the riverbed like so many teeth.

With the Old London Bridge gone, the river's behavior changed dramatically. No longer was there anything to impede the ebb and flow of the tide. The river became faster, picking up sand and gravel which had lain peacefully for centuries and scouring the foundations of the remaining bridges on the river. Within a century, the Blackfriars Bridge, the Westminster Bridge, and the Waterloo bridge would all have to be replaced.

Rennie's New London Bridge turned out to be flawed, too massive for the soft riverbed. By 1924 it had become evident that the piers were sinking. The east side of one of the bridge's piers had "dropped three of four inches below the level of the western side," by an account of the day. And the settling had only begun. So the Rennie bridge was ultimately replaced, dismantled, and sent to Arizona. (And what Arizona got wasn't much of the original Rennie bridge, which had been widened and partially covered with new stonework about halfway through its life. It was only the outer stonework that was used in the Arizona reconstruction, where it was used to cover a modern structure.)

So if you go to London today for a look at London Bridge, take a few minutes to gaze a few yards downstream. That's where the medieval bridge used to be. It's not likely to ever be rebuilt, since London has become accustomed to having its river unimpeded. As a structure, it was in its day both an engineering near-marvel and a navigational near-disaster. And like so much of medieval London, it was an essential part of the city of its time, but proved unfit to be a part of the city that London would become.

My main source for this article was the book "London Bridge" by Peter Jackson (no, not that Peter Jackson), published by MucColloch Properties, Inc. in 1971. (Library of Congress #79-170155). I've since come across Patricia Pierce's book "Old London Bridge" (2001; ISBN 0-7472-3493-0) which gives a much fuller history of the bridge, including some archeological data that wasn't available when Jackson's book was written. But Jackson's book includes some wonderful illustrations he made on some of the architectural details of the bridge, such as the construction of the starlings, so I would recommend that book as well..